by

Charles A. Bennett, Collaborator

(Formerly Principal Agricultural Engineer)

Cotton Ginning Section

Agricultural Engineering Re search Division

Agricultural Research Service

United States Department of Agriculture

Sponsored by

The Cotton Ginners' Journal

and

The Cotton Gin and Oil Mill Press

Dallas, Texas

Part I

COMMERCIAL ENGINEERING DETAILS AND DATES

Primitive and Churka- Type Roller Ginning

Neither history nor archaeology have established when mankind first began to use cotton fibers, but fabrics of cotton are quite definitely known to have been in use as far back as 4,000 years B. C. in India•a.nd probably served people long before then.

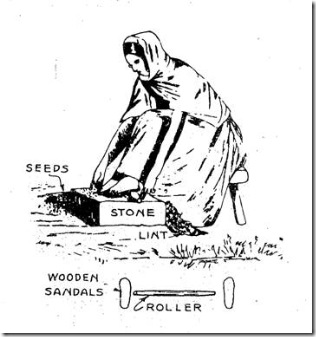

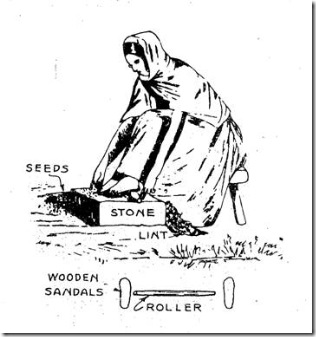

Undoubtedly the first method of ginning cotton was with the human fingers, a method that has continued in use throughout the centuries. This can hardly be called either roller or saw ginning, but it might perhaps be termed pinch ginning. The second method, believed by the author to have logically followedthe pinch ginning, is that of the archaic foot-roller somewhat as depicted in fig. I.

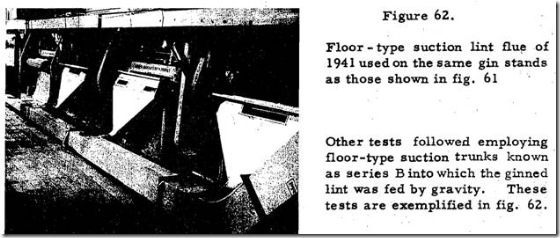

Figure 1.

Old fashioned foot-roller gin, used to a limited extent to this day in the remote areas of India.

In his 1949 report to the National Cotton Council of America,

"Cotton in Pakistan and the Indian Union", Mr. Read P. Dunn, Jr., published this figure which was credited to the East India Cotton Association, Ltd. , to whom we are in turn grateful. The observant reader will note that in this ginning method the women do the work, a practice of the western Indians as well, although the author has not been successful is putting this into practice at his own abode. Perhaps from this foot-roller idea arose that of the rolling pin and other feminine utensils.

At any rate, Mr. Dunn said that about 10 percent of the Indian Union cotton crop was ginned by primitive churka and foot-roller gins. The churka c. method of ginning, a true roller gin with small diameter pinching rollers that took the fiber from the seed without crushing, has been thought to have been named from Sanscrit whence came the term "Jerky" (which has long been spelled churka).

There are several types of the small, hand-operated churka gins, two of which are shown in fig. 2a, b, and c The diagrams give approximate dimensions in inches.

Figure 2a.

A sketch of a double crank gin with two hand cranks and no gearing.

Figure 2b.

Sketch of a single crank churka gin, made from the model owned by the late Walter Going.

The sketch in 2b shows the reproduction of the Hindu churka brought back from India about 1936 by the late Walter Going, Continental Gin Company, Birmingham, Ala. Master Mechanic Russell G. McWhirter made the replicawhich is on display at the USDA South-

. western Cotton Ginning Research Laboratory at Mesilla Park, New Mexico, where the department now centers its roller ginning research. Such a hand churka gin would probably turnout about five pounds of fiber in a long day.

It can only be conjectured as to what kind of primitive ginning methods were used in ancient Mexico, Yucatan, and Peru, as no records or models are available on the subject.

Figure 2c

Photo of a Pakistan small churka gin owned by Alfred M. Pendleton.

It is

a historical fact that, until the invention of the McCarthy gin in 1840, roller ginning efforts and ideas

were largely centered about the ancient churka type of gin, and much thought was given by the more progressive cotton growers and merchants toward attaining larger sizes and greater capacities than were feasible in the hand-operated units. Accordingly, the general development of roller ginning is henceforth listed more or less chronologically in order to present a clearer view of American activities in particular.

1742 - In this year it was reported that M. Dubreill, a French planter in Louisiana, had invented an improved roller gin that had greater length of rollers and more capacity than other gins then in use. Unfortunately we have not been able to locate sketches or detailed description of the M. Dubreill gin.

1772 - In the Mississippi-Gulf areas, considerable publicity accrued to a Mr. Krebs of Pascagoula who invented a roller cotton gin having a daily outturn of some 70 pounds of ginned lint, while competing units could only deliver approximately 30 pounds. In a history of Florida, Captain Roman of the British Army was quoted as saying that the Krebs roller gin had foot treadles and two well polished, grooved iron spindles set into a frame approximately four feet high.

1777 - At this time Kinsey Burden of Burden's Island, South Carolina, constructed a roller gin that was made from old round gun barrels. These rollers were fastened at the ends on suitable trunnions, and the unit claimed a daily capacity of 20 pounds. This unit was currently dubbed the "barrel gin," and was said to have been quite popular in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.

1790 - Dr. Joseph Eve, residing near Augusta, Georgia, introduced some form of foot treadle gin into Georgia and was given much advertisement about this time It is not known whether he employed Krebs' foot treadle drive or not. However, we here refer to the Cotton Planters' Manual (J. A. Turner) that came out in 1857 for additional information on the Eve gin. We quote from a statement made by Thomas Spalding of Sapelo, Georgia, under date of January 20, 1844:

"1st. Eve's gin was invented by Joseph Eve, who died lately at Augusta, somewhere about the year 1790, in the Bahama Islands, where Mr. Eve then resided.

"Mr. Eve was the son of a Loyalist from Pennsylvania, who had been a friend of Franklin; and Joseph Eve was himself qualified to have been the associate and companion of Franklin, or any other; the most enlightened man I have ever known.

"His gin consists of two pairs of rollers, more than three feet long, placed the one set over the other, upon a solid frame that stands upon the

floor, inclined at an angle of about thirty degrees - so that the feeder may the more easily throw the cotton in' the feedby the handful upon a wire grating that projects two inches in advance of the rollers, just below them; between these protecting wires, the feeding boards, with strong iron, or in preference brass teeth pass, lifting the cotton from the wire grating, and offering it to the revolving rollers. The feeders should make one revolution to every four revolutions of the rollers. The rollers are carried forward by wheels supported over the gin, and upon the axle or shaft of these rollers; at the center there is a crank similar to a sawmill crank, the diameter of whose revolvement is as one to four of the diameter of the wheels, carrying by bands the rollers.

"It is the crimping produced by the teeth and the wire grating, which has served as a cause for carping by the cotton buyers, and which has gradually led to the disuse of these gins, the only gin efficient for the cleaning of long cotton, which has ever been used in this or any other country. With Mr. Eve's gin, as originally sent to this country from the Bahamas, the rollers

were 5/8's of an inch in diameter, made of stopper wood, a very hard and tough wood, and they were graduated to make four hundred and eighty to five hundred revolutions per minute, depending of course upon the gait of the horses or mules, within these limits.

"Soon after Mr. Eve sent his gins to Georgia, some of his own workmen followed them, and began to make them on their own account. To show as much change as possible in the gins, besides other alterations, they increased the size of the rollers to three-fourths of an inch, and increased its velocity to six hundred times in the minute. These two changes, while they greatly increased the quantity ginned, very much injured the appearance' of the ginned cotton.

"Mr. Eve had expected and guaranteed to the purchasers of his gins when well attended, in fine weather, from two hundred and fifty to three hundred pounds of cotton in the day. I have known these altered gins do sometimes six hundred, but the injury was greater than the increased quantity warranted, add to which the quicker movement of the feeder made the more impression upon the cotton passing from the feeder to the roller.

"2d. The first bale of Sea Island cotton that was ever produced in Georgia, was grown by Alexander Bisset, Esq. , of St. Simon's Island, and I think in the year 1778. In the winter of 1785 and '86, I know of three parcels of cotton seed being sent from the Bahamas, by gentlemen of rank there, to their friends in Georgia; ;this cotton gave no fruit, but the winter being moderate and the land new and warm, both my father and Mr. Bisset had seed from the ratoon, and the plant became acclimatized.

"In 1788, Mr. Bissett and my father extended the growth, but upon my memory it rests, that Mr. Bissett was the first that found the means of sep-

arating the seed from the cotton, by the simple process of a bench upon which rose a frame supporting two short rollers revolving in opposite directions, and each turned by a black boy or girl, and giving as a result of the day's work five lbs. , of clean cotton."

1827 - Although there seems to have been little doing in roller gin improvements in the United States until this time, it was reported by William Elliott of Beaufort, South Carolina, that foot treadle gins (see fig. 3) had superseded the earlier kinds of churka gins, and that the treadle gins were being imported from the West Indies at about ten dollars ($10) per unit.

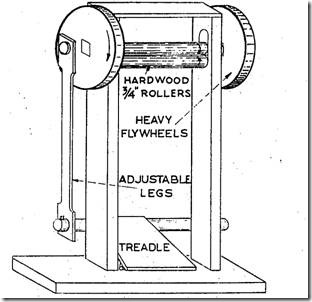

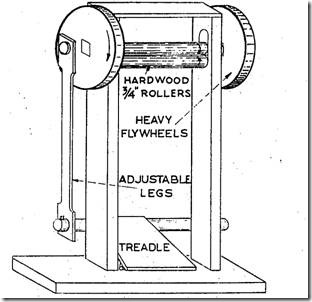

Figure 3.

Author's diagram of one form of a foot treadle churka-type roller gin. having heavy fly wheels on the top roller shaft. Other forms than this probably have been made with the two flywheels, but one being placed at the• end of each roller, in which condition the flywheels would then revolve in opposite directions and necessitate care in starting.

Referring back to the quoted article written by Mr. Thomas Spalding under date of January 20, 1844, it may be remarked that his statement is not very clear as to who unveiled the first gin, Eve or Bissett. He says that Eve's gin was the best ever, yet follows that with the declaration that Mr. Bissett was the first man that found the means of separating the seed from the cotton. If so, several centuries passed very rapidly between the time of

Mr. Bissett and Mr. Eve, because we know the churka gin is ancient, and Mr. Spalding describes a churka gin perfectly when he tells about Mr. Bissett's.

It is no wonder that a dollar went further in those days, if a man could buy even a churka gin stand for ten American dollars! Elliott said in one of his writings that tapered hardwood rollers were paired together (presumably tapered from about 5/8-inch diameter at one end to 1-1/4 inches

at the other and that with speeds well above 100 revolutions per minute the

daily ginning capacity reached approximately 30 pounds of ginned lint.

In reviewing these various statements, it seems that some ginners made up as many as five pairs of either the Eve or gunbarrel rollers per ginning unit, and that when these five pairs were used, the daily outturn was about 135 pounds of lint; but the competing Whitney saw gins were delivering 2 pounds

per saw per hour on 8-inch diameter saws, so that in a day one Whitney type saw gin delivered from 600 to 900 pounds of ginned lint according to the reports of various papers and writers. However, the mills, mostly in England, seemed to prefer roller ginned cottons when they could have their choice because there were fewer neps.

1835-1839 - William Whittimore, Jr. , of West Cambridge, Mass., began to attract attention with his roller gins. He obtained one patent in 1834 and another in 1839. Figure 4 shows the main elements of these inventions in items a, b, and c. The Charleston, South Carolina, Mercury of 1835 made favorable note regarding his gin.

Figure 4.

W. Whittimore, Jr., roller ginning inventions: a and b, features of his 1834 patent in which he employed a belt and squeeze rollers as the assisting agents in ginning; and c, the side elevation of his 1839 invention, where he used one roller made of leather disks, and the other made of roughened metal.

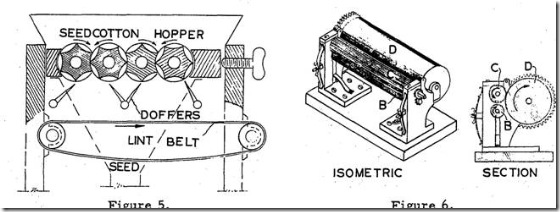

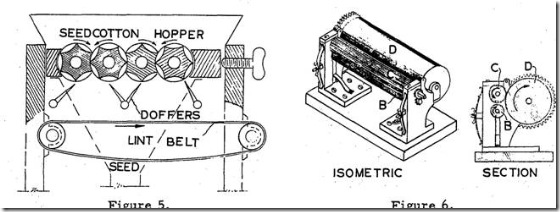

1838 - In this year an old maestro in the ginning world tried his hand at the subtleties of roller ginning, the maestro being none other than Eleazor Carver who had moved from Washington, (near Natchez) Mississippi, to the manufacturing centers of East Bridgewater, Mass. Carver had a rather clever idea in using spiralled rollers in pairs, virtually similar to gears, so that they could be fed on a flat plane for several pairs of rollers, and so that the seeds would be angered to the ends of the rollers whilst the ginned lint went down to a traveling belt. Figure 5 (on the next page) delineates in sectional form the Carver invention.

The shop construction of such rollers would have been difficult in many of the machine shops of that period, and the author has been unable thus far to locate models or reports of commercial use of this Carver gin.

Before taking up the most important roller gin invention of the century, that, of Fones McCarthy in 1840, two other inventions should be mentioned; namely, those of Richard Reynolds, Beaufort, South Carolina, and Theodore Ely, New York, New York.

Cross-section of Model 1838 Car- Reynolds 1844 roller gin: an isometric

ver roller cotton gin, which was view and a cross section, wherein

not limited to the number of pairs B and C were the ginning rollers and

of spiral meshing rollers, al- 13 did the clearing of the ginned fiber

though only two rollers are shown by taking it fromRoller B. The hand

here lever or crank is not shown here.

The Reynolds roller gin was primarily a triple roller churka type of gin having the two pinching rollers ahead of a special larger clearer roller, all as shown in figure 6.

The Ely invention displayed some genuine mechanical ability, since it

comprised both feeder, ginning rollers, and clearers, as shown in figure 7.

1845 model Ely

roller gin. This unit employed a feeding cylinder, F; a fanning or direction cylinder,

A; two fluted rollers B for ginning;and two clearers or strippers,

D. Counterweight .H provided self-adjust-

ment of pressures between ginning rollers .

THE Mc CARTHY (or Macarthy) ROLLER GIN AND ASSOCIATED INVENTIONS

On July 3, 1840, a roller gin patent was issued to Fones McCarthy, Demopolis, Marengo County, Alabama, that revolutionized the ginning practices throughout the world and especially in some countries foreign to the U. S. This new type of roller gin which his invention provided became as popular in most countries as the Whiteny saw gin was to our nation. The British refer to the gin as the Macarthy gin, but it sounds the same regardless cf spelling.

This, first patent, No. 1675, was followed by others of McCarthy, such as re-issue No. 262 of April 18, 1854; re-issue No. 1675 dated 1856; and No. 67,327 dated July 30, 1867.

In figure 8 is given a cross-section diagram of the first form of the McCarthy roller gin.

Cross-section of the 1840 McCarthy roller gin which revolutionized roller ginning by the use of a fixed blade (sometimes called a doctor knife ) held tightly against a ginning roller, and having a moving knife which cooperated with the roller and doctor knife inperformingthe separation of the fiber from the cotton seeds.

There were several other names for the parts. The moving knife, as we now call it, was termed a hacker blade because it seemed to hack at the seed which were held between the ginning roller and the fixed knife or doctor blade. The single McCarthy ginning roller was much greater in diameter than churka type rollers and hence had greater capacity from the start. Its porcupine-like surface seized the fibers and drew them

between roller and fixed blade so that there was a constant pull against the seed in order to make a clean separation. McCarthy's first moving knife had fine teeth on its working edge and was called by him the saw.

The McCarthy roller was made up of coarse leather, grooved to permit motes and other unyielding matter to pass the knife without injuring it. He also had a stripping comb behind the ginning rolls, but interposed small float and delivery rolls between the ginning roller and this comb. From what we can ascertain, the first McCarthy gins used rollers that were about 4 inches in diameter and 3 feet in length. By 1850, however, the rollers had been increased in size to almost 7 inches diameter and their lengths shortly thereafter became standardized into 3 sizes; namely, 40, 60, and 72 inches. Single roller McCarthy gins stayed at 40 inches in length almost universally until the 1940 era of

new roller ginning practices began

in the United States. Double roller gins became popular, too, and these adopted longer rollers ranging from 60 to 72 inches in most cases. Other improvements in the popular McCarthy type roller gin brought about the reciprocating pusher board, the vibrating grid for shedding seeds, the first sort of rock-and-roll link between moving knife crank and a secondary center to facilitate cleerance and afford better action in ginning, and the revolving stripper roller to wipe ginned lint from the roller.

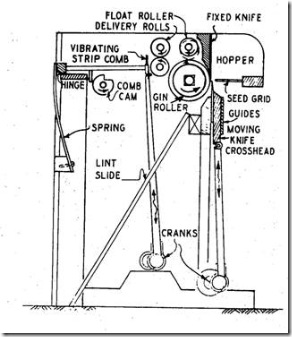

For years, however, a stationary brush stick or plain scraper bar combed ginned lint from the roller and was popular because of its cheapness. Figure 9 gives a section through the conventional gin of 1900 that was sold internationally by many well known firms.

Cross-section of McCarthy roller gin as of 1900, drawn by Professor D. A, Tompkins and lettered by author; A, main section through roller gin; and B, enlargement of the roller, moving knife, and other ginning elements employed in the 1900 McCarthy model.

Figure 10 on the next page, is a photo-reproduction from sales catalog literature that is representative of almost all better makes of the McCarthy type roller gins in the 40 inch single roller size between 1900 and 1930. American and British manufacturers had also gone to the making of double roller gins.

A,

A, delivery side (with hopper removed) of an American McCarthy type roller gin; and B, front or feeding side. Courtesy of the Continental Gin Company.

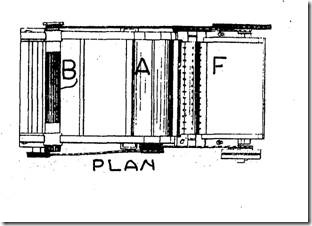

The British Middleton model of double roller gin retained the shorter roller that was virtually interchangeable with single roller gins; but the American Foss model double roller gin generally used 60-inch rollers. The approximate overall dimensions and characteristics are delineated in the plain line sketches of figure 11.

Double roller cotton gin of the McCarthy type: Figure Ila, American made 60 inch "Foss" sea-island gin. The diagrams and dimensions were taken from research units of the U.

S. Department of Agriculture Southwestern Cotton Ginning Research Laboratory, Mesilla Park, New Mexico.

Double roller cotton gin of the McCarthy type: Figure 11b, British-made 40 inch Middleton gin. The diagram and dimensions were taken from research units of the U. S. Department of Agriculture Southwestern Cotton Ginning Resea.rch Laboratory, Mesilla Park, New Mexico.

Much could be said about the advantages and disadvantages of the McCarthy type roller gins which have been in almost world-wide use for many years. They have usually been lower in cost than saw gins and have been more readily operated by unskilled labor, and on all varieties and staple lengths of cottons, regardless of whether the cottons have smooth or fuzzy seeds.

Saw gins, on the other hand, are not universally adaptable to all cottons. They have not served well in ginning sea-island or American-Egyptian long staple cottons, and their ginned lint has met with objections from the cotton mills. They blend the cotton fibers much better, however than do roller gins.

Capacities of the McCarthy type roller gins are usually far less than saw gin stands of equal floor space. For example, in the United States a roller gin usually produces from 1 to 1-1/2 pounds of ginned lint per hour per inch of roller length or from 60 to 90 pounds for a standard 40-inch roller length; while a saw gin having 12-inch diameter saws will deliver 9 or more pounds of ginned lint per hour for each inch of the saw cylinder net length, since the saws are usually set on approximately 3/4-inch centers. Thus, a saw gin has about 5 to 7 times greater capacity than a roller gin of equal length.

Small McCarthy type cotton gins for laboratory use and cotton genetics work usually are to be obtained in 8-, 12-, and 16-inch roller lengths. Figure 12 on the next page illustrates a British made 12-inch roller gin, and figure

13 shows a cross - section view of the late J. S. Townsend design which is used for governmental purposes in both 8- and 16-inch roller lengths.

Figure 12.

Hand roller gin with 12-inch roller. Courtesy of Platt Bros. , Ltd. , Oldham, England.

In setting up American roller gins between 1900 and 1930 it was customary to frame a row of vertical heavy timber posts to provide bracket supports for the feeders and shafting hangers. Figure 14 is a line drawing showing such a typical gin stand and timber set-up.

End elevation diagram of roller gin stand, draper feeder, overhead feeder, and timber posts as used at roller gins. Courtesy of the Murray Company of Texas, Inc.

Interesting factory line isometric drawings of 1917 are shown onthe next page to indicate the type of roller ginning equipment that was generally used during the period of World War I. The three figures, 15a, 15b, and 16 were lifted from the repair handbook of The Murray Company by the author

who deleted numerals in order to make small size illustrations for the pur-

pose of this report.

pose of this report.

Isometric sketches of McCarthy roller gin stand and feeder, 1917 model units; A, the gin stand proper; and B, draper or spiked belt feeder that was usually interposed between the ginning roller and the overhead cleaning feeder to give more uniform and slower feeding at the working zones. Courtesy of The Murray Company of Texas, Inc.

Isometric sketches of McCarthy roller gin stand and feeder, 1917 model units; A, the gin stand proper; and B, draper or spiked belt feeder that was usually interposed between the ginning roller and the overhead cleaning feeder to give more uniform and slower feeding at the working zones. Courtesy of The Murray Company of Texas, Inc.

Figure 16.

Isometric sketch of 1917 model overhead small drum cleaning feeder as used in ginning Pima cotton. Courtesy The Murray Co. of Texas, Inc.

Since the floor plans of roller ginning establishments have varied a great deal, they will be shown in a later section of this article. However, views indifferent roller ginning plants that operated between 1930 and 1950 are here shown in figures 15 to 17 inclusive.

In most of these ginning plants the heavy vibrations of the roller gins

necessitated sturdy sills set into concrete at ground level. Cleaning and other auxiliary machinery has likewise been kept as low as possible, although balcony installations of smaller extracting and cleaning units are comparatively common.

From previous descriptions of the older roller gins of the churka type, it is evident that they were either hand or foot operated. Oriental McCarthy type roller gins have also been similarly powered, and for smoother operation the treadle gins of all kinds seemed to be forced to the use of heavy flywheels. However, very small churkas and the present day laboratory gins may be obtained for hand drive or for electric motor propulsion. The motors have usually ranged from 1/4 to 1 h. p. for roller lengths that vary from 8 to 16 inches.

In the United States limited water power provided means for cotton gin propulsion at a few fortunate locations, but steam engine drives became common until the supply of wood became scarce or other fuels became too expensive, after which electrical and internal combustion engines took over the field. However, natural gas and fuel oils were and still are being used at some steam-powered gins where steamboilers are retained for various reasons.

A few steam-driven threshing engines served to run small cotton gins, while both portable and stationary internal combustion engines of various kinds have been pressed into service. Farm tractors also still provide temporary power for some of the smaller cotton gins in the United States,

although such roller ginning establishments are few in number.

Power requirements for commercial McCarthy type gins vary from 5 hp. for a 40-inch roller gin stand plus small drum feeder (refer to figure 14) to as much as 25 hp. per gin stand unit in larger roller ginning establishments that utilize extensive accessories and auxiliary

equipment. A simple rule of thumb applying to a roller gin stand only is, for commercial gin, to allow 114 hp. for each lineal foot of roller length in the stand, plus 1/2 hp. for each spiked belt draper feeder (refer to figure 15b). Power consumption of other ginning auxiliaries such as conveyors, fans, separators, driers, cleaners; extractors, lint cleaners , and presses are tabulated in cotton ginners handbooks or obtainable from the manufacturers of ginning machinery.

The principal elements of the McCarthy designs that revolutionized roller ginning have already been set forth in Figure 9; namely, 1, the ginning roller; 2, the fixed knife whose working edge bears heavily against the ginning roller at its axis centerline; 3, the reciprocating moving knife which has an arcuate stroke across the working edge of the fixed knife; 4, the seed grid; 5, the pusher board for feeding seed cotton against exposed roller surfaces between the movingknife strokes; and 6,

the doffer which clears ginned lint from the ginning roller surface.

Between 1840 and 1900 a surprising number of patents were granted on improvements suggested for one or 'more of these major elements in addition to the patents that have been listed for McCarthy himself. These inventions endeavored to overcome some of the roller ginning troubles such as the destructive vibration of unbalanced moving knives

, difficulties in adjusting and

maintaining overlap and clearance settings, ginning roller bending or lack of stifiaess, Short life of roller covering, and

seed crushing or chipping.

A few of the inventions prior to 1900 will be only briefly mentioned without illustrations. From 1900 to 1957 we have more fully described and illustrated the inventions that are deemed to

be of significance as contributing to the field of roller ginning. Foreign inventions and patents are note fully covered because of the lack of reliable information.

1861 - James F. Furguson, Miconopy, Florida, advanced ideas for improved rollers by using spiral winding, together with better ginning by having a more adjustable fixed knife and a vibrating moving knife whose working edge corn-, prised a row of alternating long and short comblike teeth. From that time on some roller gin inventors began to toy with all three ideas in different ways.

1862 - 1881 - The following list of roller gin patents is givenfor references without description because they do not seem to have introduced significant • changes in the arts of roller ginning.

And, second, he made up a 4-bladed stripping roller or doffer to operate adjacent to the ginning roller. The blades were at right angles to the rotation. It may be that these disclosures led to rather wide adoption in foreign countires more than in the United States because Egypt in particular had plenty of soft leather from their water buffaloes.

1892 - J. R. Montague et al, Syracuse, New York, went back to rather elaborate churka roller ginning ideas in their design, using a vertical pair of small and large rollers, a fan suction, and several other elements, making the unit quite complicated. This patent, No. 485,015, was issued. October 25, 1892, and was granted 15 claims. No reports are available as to whether a roller gin was actually constructed in line with these designs.

1894 - D. F. Goodwin, Valdosta, Georgia, made a design for a double roller gin in which one roller was placed above the other, but employing the standard McCarthy reciprocating knife and other conventional features. For reference, it may be noted that he was granted U. S. Patent No. 530,941 on December 18, 1894.

1895 - Although other inventors seem to have tried out segmental moving knives on long roller McCarthy roller gins, J.E.Coleman was granted a patent on one phase of the idea.

1895 - J. Daig, Gainesville, Florida, brought out an important improvement in fixed knife adjustment for McCarthy type gins. His invention was that of using two special springs that would hold the fixed knife firmly against the roller at fixed pressure. This idea was tested at the U. S. Department of Agriculture Cotton Ginning Research Laboratory, Stoneville, Mississippi, and was found to have considerable merit. A pressure of 30 pounds per inch of fixed knife against the roller gave optimum results. Martin, Townsend, Walton, and Baggette conducted most of the tests during the years 1941-43.

1895 - S. L. Johnston, Boston, Mass., designed a roller gin that was up-

side down to the McCarthy conventional design. He reversed the position of

the fixed and moving knives and added a sort of comb at right angles to the moving knife blade on the cotton feeding side so, that it would stir up the seed cotton better.

1899 - J. W. Graves, then a resident of Little Rock, Arkansas, designed a multi-roller gin. However, his radical design will be illustrated in the 1900 group to follow.

1900 - In this year J. E. Cheesman, New York, New York, organized the Cheesman Cotton Gin Company to promote his several roller ginning inventions and designs. He brought out a single roller gin stand on these patents

- about 1902 for public use. This unit was rather highly publicized. In it he had reversed the position of the knives as was done by Johnston in 1895, but he went all out for eccentrics in place of cranks, and he employed a whole series of

relatively short, eccentrically driven moving knife segments in lieu of one blade. Along with this, design of gin stand, which had cast iron end frames and was largely of metal otherwise, Cheesman used a small-drum cleaning feeder with regulated flow of seed cotton. The feeder was not a basket type that came later for saw gins but was an almost 25-year advance over other feeders then being built.

The Valdosta (Georgia) Times, under date of July 18, 1902, was quoted in some advertising pamphlets as saying that 32 of the Cheesman gin stands were being installed at the Valdosta Ginning Compahy which would then be the largest American Roller Ginning Establishment and that it would

be able to gin out more than 100 bales of sea-island cotton per day.

About 1909 Cheesman delivered a special address to the American Cotton Manufacturers' Association in which he detailed a cross-section design of his improved roller gin being manufactured under the 'name of Empire Duplex Gin. The construction of this second unit of his is shown, in part, by the diagram section given in figure 22.

Figure 22.

Sketch depicting a cross-sec-

tion of Cheesman's Empire Duplex Roller Gin, showing the rotary comb moving knife inlieu of his segmental reciprocating blades in the 1902 design.

Inquiries have not yet revealed whether there are any of either of the Cheesman roller gins in existence at this late date; but his feeder design and the use of eccentrics were a practical improvement over previous practices.

A reference to fig. 22 will also indicate another far -sighted improvement of Chessman's that lapsed into obscurity for many years. It was his use of large steel pipe cores for the foundation of the roller wood and covering.

This design would not only eliminate buckling and whipping at higher speeds but also would materially stiffen and strengthen long rollers. With such de- Sign the shearing of drive shafts onithe rollers could be easily overcome.

Also in 1900 an active figure in roller gin design was Matthew Prior, Watertown, Massachusetts, who used the upside-down McCarthy idea but, experimented over several years with metal ginning rollers and oscillating moving knives of the comb type. One feature that he patented. in 1900 was that of an agitating feed bin, at the bottom' of which was a reciprocating comb. knife. These and other items are shown in the diagram of fig. 23. Among the several roller gin patents that Prior obtained, one that is described for the year 1911 may be ofinterest.

Figure 23.

Diagram section of Matthew Prior Is 1900 model raler gin, having an eccentrically driven hopper side with moving comb knife at the bottom, a rotating clearer or agitating cylinder with stub paddles, a fixed knife placed in an almost horiontal plane, and a seed grid opposite the clearer.

During 1900 3. W. Graves, who seems to have moved from Little Rock, Ark., to Covington, Tenn.,

between inventions, introduced a

novel idea for roller gin construction by using hinged knives so that the fiber

could be blown between them and the ginning rollers at timed intervals or bites. Graves did not use a rotating or reciprocating moving knife for push-

ing the seeds from the doctor blade (another name frequently used for the fix ed knife, but he did use small

perforated rollers above the ginning rollers, and he operated the hinged blades by exterior cams. Figure 24 is a diagram section of the Graves roller gin idea.

As the

entire gin stand of Graves

was somewhat elaborate the reader is referred to U. S. Patent No. 655, 734 issued September 11, 1900, for further details. Although figure 24, shown on the next page, does not indicate some features of Graves' invention, it is well to call attention to the fact that the bites of his hinged blades were in sequence, depending upon how many rollers

were used, and that the seed cotton entered into the main hopper through a sealed wheel so that air pressure might be exerted through the perforated", small cylinders and blade gaps.

Figure 24.

Model 1900 Graves duplex ,roller cotton gin shown in cross-section diagram to illustrate the principle Ei employed.

1901 - At San Antonio, Texas, W. H. Wentworth submitted as his invention a fully vertical, roller cotton gin. In. his design he used six vertical ginnin rollers, six vertical fixed knives, and six vertical knives that reciprocated horizontally to reproduce the conventional McCarthy action, plus other vertical elements such, as frames, chutes, and the like. \A. central core supplied seed cotton to each ginning compartment, and all moving elements were propelled by internal and external gearing located about the circular casing.

The patent figures indicate a roller gin of size suitable for laboratory use, but with sufficiently. large gears it would have been possible to make a 6-roller ginning unit in relatively small floor space. Since a suitable illustration of this invention is not available for reproduction here, the reader 'is referred to U. S. Patent No, 668,470 issued February

- 19, 1901. 'It is believed that the Wentworth roller gin is the only vertical gin of its kind on record.

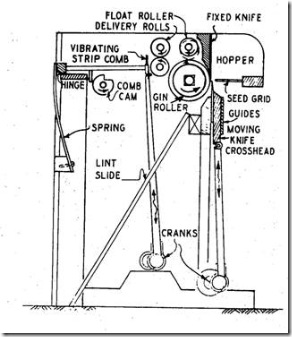

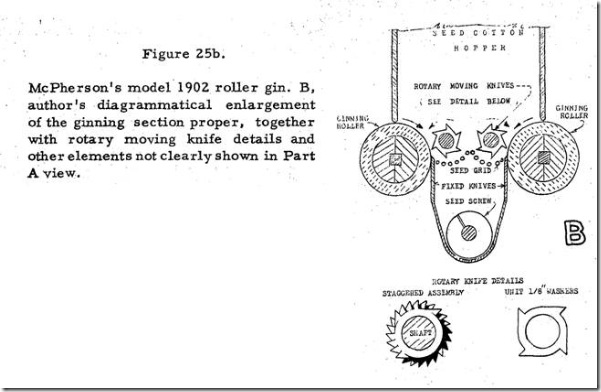

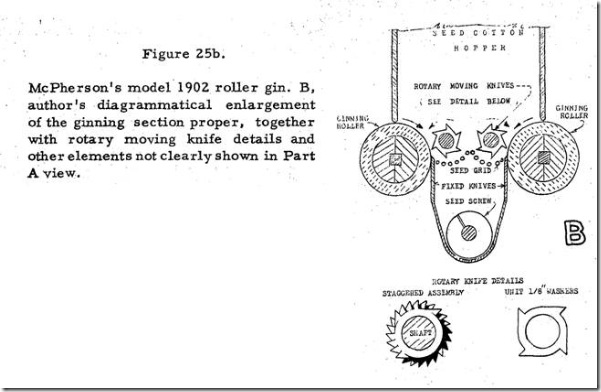

1902 - C. J. McPherson, South Framingham, Massachusetts, devised a very elaborate roller gin combination that is partially depicted in the two sections given in figure 25. This invention was the first of several duplex roller gins along this general order.

However, McPherson evidently had the spinning mill practices in mind because he sought to convert each roller gin stand into a combination of spinning mill blender, airborne feeder, and ginned lint belt conveyor all in one which would have been, in cost at least, out of the reach of most commercial roller gin operators.

1903 - Multiple roller gins were by this date no novelty although the records show very few conventional McCarthy gins having more than two rollers . However, A. M. Dastur, Jalna, Hyderabad, India, invented a 4-roller gin stand and obtained an American patent on it When viewed from the end of the gin stand, his rollers were positioned in a sort of vee relationship so that all four moving knives might shrug on a common rocker assembly. Overlap had to be the same for all four fixed knives, and to obtain satisfactory distribution of the cotton to all rollers Dastur employed small kicker rollers, one on each side at the top of the common cotton hopper that lay between the vee form of rollers. In case the reader is interested further in this Indian patent, he is referred to U. S. Patent No 736, 227 issued August 11, 1903.

T. Brandon, New York, New York, during 1903 obtained a patent (No. 731, 273) on a roller gin that used eccentrics in lieu of cranks for the moving knife, and he employed a sliding stripping comb across the face of the moving knife. As several other inventors have presented ideas somewhat along the same lines, some of these will hereinafter be mentioned and illustrated.

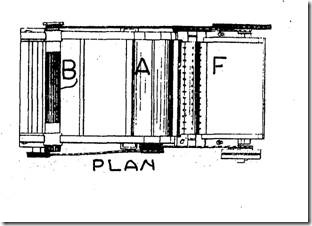

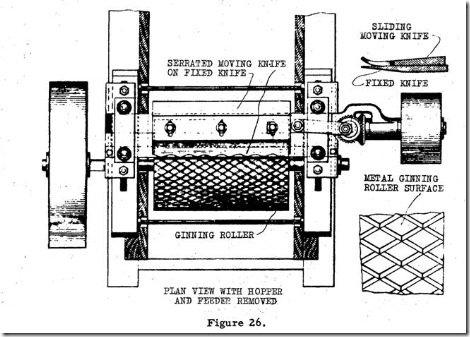

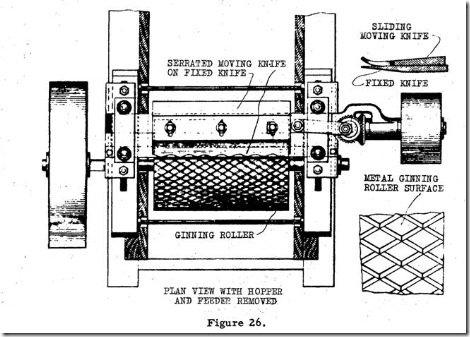

1910 - J. C. Boesch and J.H. G. Von Oven, Charleston., South Carolina, invented an ingenious combination of moving and fixed knife for their roller gin, which also had a metal roller with diamond grid indentations on its surface as shown in figure 26. The sliding moving knife reciprocated sideways along the fixed knife.

Plan view of Boesch model 1910 roller gin with side details of the knives, and roller. Collar button type of retainers held the sliding serrated moving knife in alignment along the surface of the fixed knife. This gave a mowing machine action, so to speak, for the serrated knife. The inventors claimed that the diamond indentations readily seized the cotton fiber.

1911 - Matthew Prior, Watertown, Massachusetts, was previously mentioned for his model 1900 roller cotton gin. In 19.11 he constructed models and obtained a patent on an upside-down arrangement of the McCarthy type roller gin, the position of the knives being reversed so that the moving knife reciprocated downwardly from ove rhe ad . In place of a straight blade moving knife, however, he employed the comb type for which he claimed much in actual practice. The model of this invention is now at the Southwestern Cotton Ginning Research Laboratory, Mesilla Park, New Mexico, where the United States Department of Agriculture conducts the roller ginning research. In 1938 when the author had the pleasure of visiting Mr. Prior, who was then almost 80 years old, he learned of Prior's roller ginning activities in the Orient. Prior claimed that bronze rollers with a fine-grained roughness were the best constructions he knew of, but he had obtained excellent clingability for roller surfaces by using alternate layers of grass cloth or haircloth fabrics and canvas pressed into strips somewhat like pump packing and then wound spirally around the roller. Prior also used a 4-flap

rubber doffer to remove the fiber from his ginning roller. A small Townsend 8-inch Government model roller gin, obtained about 1941 by Deane Stahmann of Las Cruces, New Mexico, was turned upside down

Prior fashion, and it has been claimed to do very fast and good work.

1913 - S. D. Shepperd, Neward, New Jersey, came out during this year with a very well designed duplex roller gin whose cross-sectionis shown in fig. 27. In. this design Shepperd used rotary moving knives that were constructed of 3-tooth washers which were strung and keyed to their shafts. Plain washers of small outside diameter were placed between the toothedknockers so as to give a combing action as well as a moving knife separation of seed from fiber.

Section through 1913 model Shepperd duplex roller gin. Note the duplex seed grids and rotary moving knives at each side of the section with the lint flue central.

The Cheesman gin of fig. 22 had a similar form of rotary knife, as did McPherson's 1902 duplex model.

1914 - To obtain better balance and moving knife action, E. G. Trepani, of Liverpool, England, and Adana, Turkey, obtained a U. S. Patent on his idea of using double segmental moving knives to which he added a secondary thin set which oscillated sideways between a heavier moving knife and the fixed knife. He claimed a better balance and a double ginning action.

1917 - The elaborate designs of W. T. Dodd, Brooklyn, New York, during

1917 added another duplex roller gin that could be classified as being of the McCarthy type but which differed from previous inventions such as those of Graves and Shepperd. Dodd, like Cheesman, used a cleaning feeder, but here it was a dual cylinder unit and fed down upon a splitter to serve two rollers. Knocker-type rotary cylinders served as moving knives, and an air blast from beneath the ridge served to keep the fiber stripped from the ginning roller and directed downwardly into a dual gin flue system where the lint was conveyed pneumatically to the press. Figure 28 gives a cross-section of the Dodd unit which will be readily understood.

1922 - Although we have no suitable illustration of the invention of W. W. Conway, Hum-bolt, Arizona, it appears that he invented a churka type of roller gin that was somewhat similar to the Whittimore 1835

model as he depended upon a belting surface and rollers to do the ginning. However, he had a horizontally raking spreader to keep the seed cotton uniformly spread at the gripping point of the belt and roller. Conway was issued U.S. Patent No 1,408, 343 on February 22, 1922. While his gin probably did not have the capacity of the conventional McCarthy, the design would seem to be superior to an orthodox churka roller gin.

Also in 1922 James C. Garner, Houston, Texas, well known for his regin and other cotton machinery inventions, was granted a patent on a very interesting principle of roller ginning that utilized suction in its operation. Figure 29 gives a diagram section of the principles advanced by Garner for this gin. The diagram will show that the action centered upon a perforated roller through which the ginned lint passed enroute to the gin flue. Below the centerline of this ginning roller Garner placed his fixed knife and diagonally above the fixed knife he reciprocated horizontally a comb form of moving knife. If and when ginned lint did pass through the walls of the perforated ginning roller, it was pneumatically carried to the ends of the roller and there discharged in

an auxiliary flue to the main lint stream. Although the author enjoyed many contacts with Mr. Garner on re-ginning and other problems, he was not informed as to whether this suction roller cotton gin was put into field use for any length of time. It is probable, however, that it was thoroughly tested by Garner because he was a practical ginner and ginning designer who was not content to leave his inventions in a paper stage.

1923 - H. E. Werner, Houston, Texas, followed Garner with another form of suction roller cotton gin on which he obtained U. S. Patent No. 1,452, 667 that was issued April 24, 1923. This patent specification gives a voluminous description, illustrated by 28 figures, but there has been no record of its use by the trade. The designs show a built-in fan, hollow perforated suction rollers to grip the fibers so that a fixed knife would do the work without need for a moving knife. No figure is available for this invention.

1924 - H. Cross and A. Korosinki, Naberth, Pennsylvania, were in this year the Patentees of a very unique design of roller gin. In general it followedthe McCarthy principles, but it employed a cylindrical moving knife of zig-zag cuffs on a central tube, much like the sleeves of the French dandies in the time of the Three Musketeers. The fixed knives were sections, built up to make one rigid unit, and the ginning cylinder was of rigid design being formed upon a central pipe with wheel and spoke ends. Two details have been here shown as parts of fig. 30 in an effort to convey the major details of this peculiar roller gin. A special feature of this invention seems to have been the roll-box action that would be obtained by the zig-zag disks which formed the moving knives. These were spaced apart by cast washers having the same contours so that pockets were formed between the disks wherein seed cotton could be carried around until fully ginned.

1925 - As a sort of unclassified form of cotton gin that was strictly neither roller nor saw, but de serves mention at this point, is the 1925 posthumous patent granted to the estate of W.E. Collins, of Houston, Texas. Mr . Collins used two large grooved drums arranged so that an endless wire could form upper and lower grids between the two. These wires ran approximately 3/16 of an inch apart. The lower plane of wires were fed seed cotton frombetween the drums. This seed cotton was then carried toward one drum where the seed were pinched out between the wires while the fibers were gripped in the drumgroove

s.

On the upper and outer surfaces

of the ginning drum, final separation took place between seeds and ginned fiber and the mechanisms. (U. S. Patent No 1, 547, 164 dated July 28, 1925).

1928 - As the state of Arizona has long been an intermittent producer of long staple cottons, its roller ginning history has likewise risen and fallen into activities and idle seasons that were not conducive to rapid improvements in roller ginning processes, even if it at times did lead therein. The roller gin invention of Gus Talley (U. S. Patent No. 1, 678, 794 of July 31, 1928) marks an interesting development. In addition to reversing the conventional position of the fixed knife, Talley brought out a cycle-bar or mowing-machine type of crank-driven knife that moved horizontally along the face of the fixed knife, as did Boesch. The machine design was of high grade craftsmanship and the relatively high cost of the ginning unit may have precluded its extensive use because the claims for its improved operation seem to have been numerous.

Neither photo nor suitable drawing is now available for illustrating this gin, but information has been given that there is a complete Talley gin in existence at Phoenix, Arizona.

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjoUI8D5ZT-1v_W7WCJkSdho-DQMURtyj6B31Igv9QEPsxa3wSvd4pTAZGNl2QpU2IKwTpvmFrjB_5UH1W2fGKU4wMWFZ7nO3v_AKZPDZKhTGDZ_MuiybAFYsu2eyToM0NmMcoHSU80Lc7l/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image004[4] clip_image004[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgRlyQMRJGHF4NXXS3k2KD2duYPvOGrLOuGQQmyLh7vPy-fU3VP9u9YcK_2mkg3A7fiIujrILq9UELdksceU1_-oreFj2VEl4h-L_Sz4Mzs4mddaVOVZnhGXUqup80SXitRV2cBjeVQAbUf/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image006[4] clip_image006[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjyNEvYbTo94JAIgsm8jkA-40YKyjc8tNATx5IKHdRRAeNZ6aa31Z9C2SwwGCTbBNa78lYSRlDKjNVFSAy0poursrvzQzaZHBADkGdMDafg0kGlRfCOVusuND3urH8wTaN1pqLOo6gkDriH/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image008[4] clip_image008[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgcjpuj0Pi-SAkMAct4i1_s-ul04X919kN8pvlXxieNr3MRtSZMgR2VDCSO79nLDyIR4grmgtBnkNijBSrGM9tvtU8vUuTdH5gTQs5tYk05FTpCB4N6cbGco9tiERyp2HrlexkEhwmOhMQM/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image010[4] clip_image010[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjoUHdOu8S-pZ-UfiHAgbKdbjcFt-gjAz29fsjwzR90ZxDSg3XDavhyphenhyphenrFjXnaNFaQEXMfubO6rqq5pmfph03hoSLvMEl4E4InjUUgAsor0Di-hZZqv2-cA7dfkTNEietrhCM05G6VT1SqzH/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image012[4] clip_image012[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgwcIikizSGwFTOApxACp2ZLJC1Td9PuzdtjNSeiGRb80r3Iu3hzMR4BzYEJR7FVHGrojNyvPujl1Qd7VkBdGSKUUapwEQcEo1lekvNUF2eZAXyiMkubM7g9Op6fE1GVMNcmfbgVaSh0SQk/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image014[4] clip_image014[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg7qDWlTiMBXR5T3rWCDlJN-Muz65MT36OL6wl_XbRzRXCjnx_5QX8OkRTKoJjh99C-01KLQyage05vw3Q2tsE0ngedtMVxGO0APiUsQEAfhDLUMCPop9sBsefaT-4mmGviLY3_tLu0Gzzv/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image016[4] clip_image016[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiLF3j16qFjZuzL6lsA_4IURcK3NBZFgCp8WPd_iW6XXw6kA_DS2c_cAjQspS8d9c9K5Fc8mQmoDFdPMf-VfNn06WmpKODdjb4wP0hFYiJCdmV6qsathH4f00ZqNjhKiC3Lzu9977tlsNtT/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image018[4] clip_image018[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgRF5Wuv36KtjOq_kudoHK3Mb-SEgEtY9Renzk_XjTku15rM8x0-iEah0k4jLvgQCCPCw6wqAakxEk3yvZHkpI2uNRU1Vs211W2BhKOfdcoHX1-xcnSVBYSKspZu8eW_8xW5Wrv64hDv-jo/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image020[4] clip_image020[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjh7grOmQSis_VJUzkIaohppkSmeU-FIMWDNeMNbD15psXObtDKzM0HdNr7goDDgkfKtZNu0xbK6onV-Jy82sCr3G_P2Tvnzun7AzpNcCbvDH8MFm2o_zZX-x7j_SpIFJb97Q62wkJkRQ-K/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image022[4] clip_image022[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh0z2Dv9VOD2RU4bL1u6wAx_pa5cjM6jOEmQTgSNrkaIdRlA3d5F16Xes7IwSjc_m_3tZ4Z8wDsol7eW1v9t2StuukA_itbAK_UTfvH0j96PKW71pGuby8_qBC8g02q7dNDtgvOEOcPB362/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image024[4] clip_image024[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEizW-PbfjPiEodws2xt8HNThxRsM5pOjZX1rCTxiLOKBiJe0ioBZC4qbgdoXMEHmNE5pHQ1REEsNL949HEuiuLlQ1vPj7wyKp1oWjQE5kryRd-7YlvNfH6ewuQMfpIe6LZLcBKc_pNh7xNo/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image026[4] clip_image026[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgqmW-1QEbxEF7Jxxhzmbjvt5K_DGw_9Ddu1bnOZKaqKUNlXyGQLEz8J3ObnKQB0gx30k1AL_42UF-jM46RiPo9wfwCNjZWCp_IAivWrwoox9x3AMhqdKTHgAiUuEdVlo7jRgRlqqKm9u1c/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image028[4] clip_image028[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi9A71n3Uz9k70qcDTskMf2BKOy8_t80WK-SblcCBKF5eIIGgyyO7-P_YKAO4ptBQJO-ml95WGYaeqHahDRHHD_2aKC9wsYCvtDHac-L7FLd8LDByLS0DhwqJe9E8LaQIlzY3olFADoTYlU/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image030[4] clip_image030[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_4T1IAyhjMOadjb2zWIms452lrOuiXiuDa-jL6_7komcrubXKDcbDYQ5NOJyF94mMMZAfKRicnvoNo0qCX-jC5sGRo9x5KvrgoKjkjTw3WQ3dwCpjByxbCr6p4HKJzCW5TmxoSz8ui0a1/?imgmax=800)